Publications

Publications

Squandering an Opportunity. This article summarizes twenty years of squandering an opportunity to save a magnificent bird from extinction. The Ivory-billed Woodpecker has repeatedly been thought to be extinct only to be rediscovered during the past hundred years. The most recent rediscovery was announced in an article that was featured on the cover of Science in 2005. It was the first time in several decades that ornithologists reported this remarkably elusive bird. Despite a subsequent report of sightings by another group of ornithologists, the persistence of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker became controversial when neither group managed to obtain a clear photo. Between 2006 and 2008, I obtained video footage during three encounters with Ivory-billed Woodpeckers. The videos show field marks, body proportions, flights, and other behaviors that are consistent with the Ivory-billed Woodpecker but no other species. This evidence should have resolved the issue, but there was a breakdown in rational discourse after naysayers became entrenched in the position that the species is extinct. As discussed in this article, there has also been a breakdown in editorial oversight, which has allowed the naysayers to mislead the public about the status of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker without addressing the strongest evidence for persistence. The articles listed below discuss the videos and other information relevant to the conservation of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. The analysis of the videos has been consolidated in an up-to-date summary.

“Putative audio recordings of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis),” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America (2011), pdf, supplementary material.

“Video evidence and other information relevant to the conservation of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis),” Heliyon (2017),

pdf.

“Periodic and transient motions of large woodpeckers,” Scientific Reports (2017),

pdf.

“Using a drone to search for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis),” Drones (2018), pdf.

“Statistics, probability, and a failed conservation policy,” Statistics and Public Policy (2019),

pdf.

“Application of image processing to evidence for the persistence of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis),” Scientific Reports (2020),

pdf.

“The role of acoustics in the conservation of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis),” Journal of Theoretical and Computational Acoustics (2021), pdf.

“A science scandal that culminated in declaring the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) extinct,” Journal of Theoretical and Computational Acoustics (2022), pdf, supplementary material.

“Update on the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) scandal,” Journal of Theoretical and Computational Acoustics (2023), pdf, supplementary material.

“A resolvable controversy in avian conservation,” Heliyon (2024), pdf.

“Comments on ‘Echo of extinction: The Ivory-billed Woodpecker’s tragic legacy and its impact on scientific integrity,’” BioScience (2025), pdf.

Observations and Evidence. Between November 2005 and June 2013, I spent several months per year searching for Ivory-billed Woodpeckers. Most of this effort concentrated on areas near English Bayou (which appears in the above image) in the Pearl River swamp in Louisiana, where I had nine sightings and obtained video footage during two of the encounters. I have posted video presentations of the evidence and other information relevant to the conservation of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, drone footage of the swamp forests where the videos were obtained, and daily logs for the 2006,

2007, 2008,

2009, 2010,

2011, 2012, and

2013 search seasons and for

visits after 2013.

The 2006 Video. I obtained the first video during a five-day period in February 2006, when I had five sightings and heard the ‘kent’ calls of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker on two occasions (once coming from two directions at the same time). The video shows a perched woodpecker that dwarfs a Pileated Woodpecker specimen, is comparable in size to an Ivory-billed Woodpecker specimen that is near the maximum size for that species, and has several characteristics and behaviors consistent with the Ivory-billed Woodpecker but not the Pileated Woodpecker.

The 2008 Video. A short distance up the same bayou in March 2008, I obtained video footage of a large woodpecker in flight. The appearance in the video of the bird and its reflection from the surface of the bayou made it possible to pin down locations along the flight path, estimate the flight speed, and confirm that the wingspan is well over 24 inches. The video shows a wing motion in which the wings are folded closed in the middle of each upstroke. The Pileated Woodpecker and the Ivory-billed Woodpecker are the only large birds (wingspan greater than 24 inches) of the region with that wing motion. An expert on woodpecker flight mechanics also concluded that it’s a large woodpecker. Since the wingbeat frequency is about ten standard deviations greater than the mean wingbeat frequency of the Pileated Woodpecker, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker is the only possibility, and the flight speed, wing shape, and field marks are consistent with that species but not the Pileated Woodpecker.

The 2007 Video. During a visit to the Choctawhatchee River swamp in January 2007, I had an encounter with a distant pair of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers that lasted for more than twenty minutes. With a high-definition video camera, I obtained video footage of a double knock, spectacular swooping flights that are consistent with an account by Don Eckleberry of a landing with a “magnificent upward swoop,” and takeoffs with deep and rapid wingbeats and ‘wooden’ wing sounds that are consistent with an account by James Tanner.

Mechanics of Double Knocks. Most woodpeckers signal with drumming, but the Ivory-billed Woodpecker and some of the other members of the Campephilus genus signal with double knocks. While studying footage of an Ivory-billed Woodpecker delivering a blow that is accompanied by an audible double knock, I noticed that there appears to be only one thrust of the body. This didn’t seem to be consistent with my expectation that a double knock is the result of two deliberate blows. While studying video footage of a Pileated Woodpecker drumming, I noticed something that led to an understanding of double knocks and how they relate to the drumming that is typical of most woodpeckers. As discussed in Movie S1 of

this article, the drumming of a Pileated Woodpecker is driven by periodic vibrations of the body, and there are a few additional blows of decreasing amplitude after the driving force is turned off. This suggests that a drumming woodpecker may be modeled as a harmonic oscillator in which the bird is anchored with its feet and tail and the restoring force corresponds to tension in the neck and body. The graph on the above left corresponds to a damped harmonic oscillator in which periodic forcing is turned on at the first dashed line and turned off at the second dashed line. After a brief transient, the response is periodic. After the forcing is turned off, there is a transient that is consistent with the observed drumming of a Pileated Woodpecker. The graph on the above right corresponds to a damped harmonic oscillator with impulsive forcing. The response is a transient similar to the one appearing to the right of the second dashed line in the graph on the above left. This model accounts for (1) the double knock in the 2007 video, (2) the double knock of a Pale-billed Woodpecker that is discussed in Movie S2 of this article, and (3) the multiple knocks of some Campephilus woodpeckers, such as those of a Crimson-crested Woodpecker in this recording.

Flights of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. According to the great naturalist, John James Audubon, the flight of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker is “graceful in the extreme.” This account indicates that there must be something extraordinary about the flights of this bird, but for several decades it appeared that specific details about the types of flights that inspired the account were lost forever. Since no flights appear in the film that was obtained at one of the last known nests in 1935, historical accounts were until recently the only information that existed about the flights of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. Several types of flight appearing in the videos may be viewed in movies that accompany the up-to-date summary. Michael DiGiorgio produced the above illustrations of flights (click here for a high-resolution version).

Swooping Flights. As shown in the illustration on the left, the Pileated Woodpecker typically swoops upward a short distance before landing on a surface that faces the direction of approach. In the 2007 video, there are spectacular upward swooping landings with long vertical ascents, which are consistent with an account by Eckleberry of an Ivory-billed Woodpecker that “alighted with one magnificent upward swoop.” A long vertical ascent allows time for maneuvering. As shown in the illustration on the left, during two upward swooping landings in the 2007 video, there is a long vertical ascent, rotation about the axis, and landing on a surface that does not face the direction of approach. A Magellanic Woodpecker makes the same flight maneuver in this video, which was obtained in Patagonia in 2025. This is a clear match of a remarkable behavior by a closely-related Campephilus woodpecker that cannot be attributed to the Pileated Woodpecker. A downward swooping takeoff that is followed by a long horizontal glide in the 2007 video is consistent with the following account by Audubon: “The transit from one tree to another, even should the distance be as much as a hundred yards, is performed by a single sweep, and the bird appears as if merely swinging from the top of the one tree to that of the other, forming an elegantly curved line.” As shown in the illustration in the middle, a woodpecker in the 2007 video takes off and accelerates with rapid wingbeats into a remarkable high-speed upward swooping flight immediately after delivering a blow that produces an audible double knock.

Cruising Flight. The Ivory-billed Woodpecker has a ‘duck-like’ flight according to historical accounts, which were incorrectly interpreted to pertain to the wing motion. In the September/October 2005 issue of Bird Watcher’s Digest, the flights of the large woodpeckers are illustrated in a series of paintings by Julie Zickefoose (an avian artist whose work on the Ivory-billed Woodpecker has appeared on the cover of the January 2006 issue of The Auk). Zickefoose correctly showed the wings of the Pileated Woodpecker folding closed during the middle of the upstroke (this wing motion is apparent in this footage). In accordance with conventional wisdom at the time, Zickefoose showed the wings of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker remaining extended throughout the entire flap cycle. After the 2008 video revealed that the wing motion of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker is similar to the wing motion of the Pileated Woodpecker (as shown in the right frame of the illustration above), it came to light that a photo from 1939 was taken at an instant when the wings were nearly folded closed. This is one of the lowest quality historical photos, and the clue it provides about wing motion was apparently overlooked for several decades. The description of a duck-like flight evidently pertained to the high-speed flight rather than to the wing motion. The bird in the 2008 video has a flight speed of 15.2 m/s, which is well above the flight speed range of 7.5 to 11.6 m/s that Bret Tobalske published for the Pileated Woodpecker. The bird in the 2008 video has a wingbeat frequency that is about double the wingbeat frequency that Tobalske published for the Pileated Woodpecker. The high flight speed and high wingbeat frequency are consistent with historical accounts, the narrow wings and high mass of this species, and the predictions of models that relate these quantities to each other and to body parameters. The wings of the bird in the 2008 video have a swept-back appearance, which is consistent with a photo from 1935 and the narrow wings and high-speed flight of this species. The wings of the Pileated Woodpecker do not seem to have a swept-back appearance during cruising flight.

Short Flights between Limbs. According to an account by Tanner, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker usually flaps its wings during short flights between limbs. This would make sense for a woodpecker that has narrow wings and is one of the most massive in the world. The Pileated Woodpecker has a relatively low mass and broad wings, and it makes short flights nearly effortlessly. The large woodpecker in the 2006 video makes a deep and rapid flap during a flight of less than one meter. According to Zickefoose, this flight is “unlike anything I’ve seen a Pileated Woodpecker do.”

Takeoffs with Deep and Rapid Wingbeats and ‘Wooden’ Wing Sounds. According to historical accounts, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker has deep and rapid wingbeats during takeoffs. This would make sense for a massive woodpecker with narrow wings. According to Tanner, the wings make loud ‘wooden’ sounds during takeoffs with deep and rapid wingbeats. In the 2007 video, there are loud wooden wing sounds during two takeoffs with deep and rapid wingbeats. During one of those takeoffs, the deep and rapid wingbeats are similar to the deep and rapid wingbeats during a takeoff of the closely-related Imperial Woodpecker; the Pileated Woodpecker has much slower wingbeats during takeoffs. Just before the other takeoff with deep and rapid wingbeats, the bird came in for a landing with a magnificent upward swoop and showed field marks consistent with the Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

Using the Wings for Balance. According to Tanner, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker frequently ‘flirts’ its wings (rapidly opens and closes them). This behavior would make sense for a massive woodpecker that uses its wings in order to maintain its balance while moving around in a tree. In some cases, flirting the wings could be regarded as a type of flight in which the wings are used for balance rather than to become airborne. An Imperial Woodpecker (the most massive woodpecker in the world) flirts its wings in the only 85 seconds of film that exists of that species. Just before delivering a blow that produces a double knock in the 2007 video, the bird flirts its wings several times while moving along a branch.

In 2007, I started using tall trees to keep watch over much larger areas than are visible from the ground. I was hoping to obtain a video of an Ivory-billed Woodpecker similar to this video of a Pileated Woodpecker flying over the treetops in the distance. The approach ended up working, but not as I had expected. In June of that year, Steve Sillett, Jim Spickler, and Michael Taylor came to the Pearl River to get me started with this approach. In this video, Steve and Jim are rigging a tree that is located a short distance up the bayou from a site where I had a series of sightings in 2006. Less than a year later, I was keeping watch from 75 feet up that tree when an Ivory-billed Woodpecker flew up the bayou and passed nearly directly below. I obtained lots of video footage and images during observation sessions in the trees, which provide stunning views of the habitats. The first step of the approach that Steve and Jim use to rig trees is to shoot an arrow attached to a fishing line over a high branch. I have used the same approach to put Christmas lights up in trees. I can still remember my first tree climbing experience, which was around 1963.

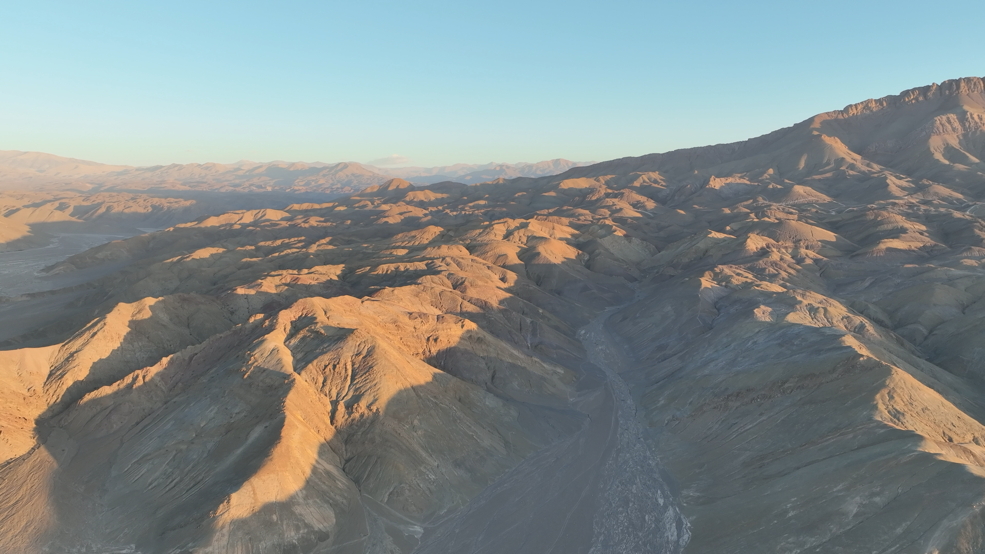

As discussed in this article, I have used drones to obtain video footage and images of habitats where there had been recent sightings of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers. In areas appearing in this image of English Bayou in the Pearl River swamp, Ivory-billed Woodpeckers were observed seven times in 2006 and twice in 2008; video footage was obtained during encounters at sites on the lower left (February 20, 2006) and near the center (March 29, 2008). In areas appearing in this image of the Bruce Creek area in the Choctawhatchee River swamp, Ivory-billed Woodpeckers were observed several times between 2005 and 2007 (one of the sightings was by an ornithologist); video footage was obtained during an encounter with a pair of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers near the center of the image (January 19, 2007). I have also used a drone to obtain video footage of cloud forest and jungle habitats in Peru (the above image was obtained near Rio Madre de Dios), the approaching shadow of the eclipse of 2017, the Hillsborough River swamp in Florida, fireworks on the 4th of July (this image is from Radford, Virginia, in 2021), an Easter egg hunt, autumn colors in the Appalachians, Palisade Falls in Montana, the Pennsylvania towns of Greenville and Jamestown, and the Virginia town of Radford.

6,118 kilometer road trip. I visited Argentina and Chile in November 2025. Click here for a larger version of the above map. The primary objectives of the trip were to observe Magellanic Woodpeckers and obtain photographs of the southern sky from Bortle 1 (extremely dark) sites with a Vespera 2 smart telescope and a Nikon Z6ii camera. There was no way to know in advance how much time it would take to achieve those objectives, but I made tentative plans for a pelagic bird watching trip to the Humboldt Current and a visit to the Atacama Desert. After flying into Buenos Aires on November 10, I rented a Toyota Corolla and did the long drive to Bariloche in Patagonia, where Valeria Ojeda had offered to take me to nests of the Magellanic Woodpecker. While in that area, I used the telescope at a Bortle 1 site to the south of Las Bayas. After finishing up in Bariloche, I crossed the border into Chile near Pucón and drove north to Valparaiso for a pelagic trip. Along the way, I stopped at a Bortle 2 site to the east of Los Ángeles. After the pelagic trip, I drove north to Copiapó in the Atacama Desert. After another night at a Bortle 1 site with the telescope, I drove across the Atacama Desert and over the 15,505 foot San Francisco Pass in the Andes. I arrived back in Buenos Aires on November 25. I came to see Magellanic Woodpeckers and pelagic birds. Despite not actively looking for other birds, I got photos of Austral Thrush, Austral Parakeet, Black-chinned Siskin, Buff-winged Cinclodes, Burrowing Parrot, Cinereous Harrier, Cinereous Ground-Tyrant, Gray-hooded Sierra-Finch, Monk Parakeet, Variable Hawk, White-crested Elaenia, and White-throated Treerunner.

Magellanic Woodpecker. In 2018, I was considering a trip to Patagonia after coming across evidence that Magellanic Woodpeckers might have flights similar to the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. I set aside those plans after being diagnosed with prostate cancer. After retiring in 2025, I got in touch with Valeria Ojeda, who offered to take me to active nests in old-growth lenga forests, where she has been studying Magellanic Woodpeckers for more than twenty years. Just before the trip, my left foot and ankle swelled up. I knew this probably meant there was a blood clot in my leg (it was later diagnosed as an occlusive clot behind the knee), but I wasn’t going to let anything get in the way of this opportunity. A female Magellanic Woodpecker appears in the above photo. A male appears in this photo. During an encounter with a pair of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in Florida in 2007, I obtained video footage of upward swooping landings with long vertical ascents. During two of those flights, the bird rotated about its axis and landed on a surface that doesn’t face the direction of approach as in this illustration. At one of the nests in Patagonia, I obtained this footage (cropped from a 4K video) of a landing that is identical to the landing in the illustration. Just after the landing, there is still some upward momentum, and the bird takes a few small steps upward. This is similar to a man stepping off a moving streetcar and taking a few quick steps before stopping. Note that the bird flies in to the left of the tree (rather than directly toward it), which sets up the landing on that side of the trunk. During the approach on this type of flight path, tree branches that could be dangerous obstacles along the ascent path would be relatively easy to see (sticking out to the side). In this uncropped image from the video, the tree on which the bird landed (to the right of the nest tree, which is in the center of the image) is the most suitable tree in the scene for a long vertical ascent along the trunk of a tree. The full 4K video may be downloaded here (Movie S12) along with other interesting flights by Magellanic Woodpeckers (Movies S13 through S16). From directly below a nest, I obtained a photo (click here for high-resolution version) that shows that the Magellanic Woodpecker has wing-tail-body proportions similar to those of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker: (1) the distance the tail projects behind the trailing edge of the wings is about the same as (or slightly greater than) the width of the wings (distance between the leading and trailing edges of the wings) and (2) the width of the body is more than half the width of the wings. In this comparison, note the similarities in the feet and crests (Tanner took the photo of the nestling Ivory-billed Woodpecker, which was later determined to be a male). From one of the nest sites, I had a nice view of Mt. Tronador. During my visit to Bariloche, Facundo Vital took me to a massive rock face that is pockmarked with caves where Andean Condors roost.

Night sky in the Southern Hemisphere. Much of the southern sky is not visible from temperate latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere. During previous trips to the Southern Hemisphere, I saw the Southern Cross and Large Magellanic Cloud. During this trip, I got my first look at the Small Magellanic Cloud, the bright star Achernar, and various nebulas. To the east of Los Ángeles, Chile, I used my Nikon Z6ii with a 20 mm lens to obtain the above photo (click here for a high-resolution version) and a time-lapse movie that shows the stars rotating around the south celestial pole over a three-hour period. Note that the rotation is clockwise. It is in the opposite direction when viewing the north celestial pole. I used a Vespera 2 smart telescope to obtain photos of various objects at sites to the south of Las Bayas, Argentina, and to the east of Copiapó, Chile. This photo shows the Vespera 2 at the site near Las Bayas. My primary objective was to obtain photos of objects far to the south that cannot be observed from temperate latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere, including the Carina Nebula, Tarantula Nebula, 47 Tucanae star cluster, Jewel Box, Large Magellanic Cloud, and Small Magellanic Cloud. I also obtained photos of the Orion Nebula and Rosette Nebula.

Pelagic birding trip in the Humboldt Current. On November 21, I went on a pelagic trip out of Valparaiso (which appears in this drone photo) with Albatross Birding & Wildlife Photography in Chile. The trip was led by Pablo Cáceres, who has many years of experience with the pelagic species of the Humboldt Current. We saw the birds appearing in this list, including five species of albatross. In the above photo, a Northern Royal Albatross is flying toward the camera, with a Salvin’s Albatross in the background. The other albatrosses were Black-browed, Buller’s, and Gray-headed. Among the other species seen were Inca Tern, Northern Giant-Petrel, Peruvian Booby, Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Peruvian Pelican, Pink-footed Shearwater, Red-legged Cormorant, Sooty Shearwater, South American Tern, Westland Petrel, White-chinned Petrel, and Wilson’s Storm-Petrel. For years, I had wanted to try using a drone to film pelagic birds, but I didn’t bring my favorite drone on this trip. I brought several cameras and lots of other gear for use at Magellanic Woodpecker nests. I took most of the items shown here (all but the tripod and Pelican case) in carry-on bags. I managed to squeeze in a Mavic 3 Classic drone but had to leave behind the much larger Phantom 4 Pro, which I had previously used at sea. I had little experience with the Mavic 3, which lacks the convenient handle of the Phantom 4 and is for that reason difficult to launch and land in less-than-ideal conditions. I didn’t realize until later that the mode selection button on the controller had somehow gotten switched from normal to cine, which caused the drone to behave in an unfamiliar way (not a good thing when launching from a boat). Even worse, the drone somehow decided to write to the small internal disk rather than to the memory card. The internal disk filled up quickly, and it stopped recording with more than 30 minutes of battery remaining. Due to this glitch, I managed to get only a small amount of video footage and didn’t have time to experiment with the altitude, viewing angle, and ISO (a higher value would provide sharper images of birds in flight); but it was nice to finally have an opportunity to use a drone on a pelagic trip. I will be better prepared next time. I have obtained an aftermarket handle that will make it easier to launch and land the Mavic. Drone footage, photos obtained with a Nikon Z6ii and a 400 mm lens, and footage obtained with a Sony 4K video camera appear in this movie.

Atacama Desert. On the final leg of the trip, I drove north to Copiapó, where I obtained this photo of the clear blue sky from the balcony of my hotel. The above photo of the barren hills in the Atacama Desert (the driest place on Earth outside of Antarctica) was obtained during a drone flight to the east of Copiapó. After a night of using the Vespera 2, I decided to start the trip back to Buenos Aires. I wasn’t aware of the difficulty of the drive across the Atacama Desert (six and a half hours with no services) and over the Andes (15,505 foot pass). The landscape in the Atacama Desert is painted in many colors, as can be seen in this satellite image (Copiapó is to the lower left; Laguna Verde and the pass at the border are to the upper right). I started the drive in the middle of the day and wanted to be sure to arrive at the border station before it closed. To save time, I passed up many spectacular photo opportunities that arose as the colors changed around each bend. I made only a few stops and got photos of Laguna Verde and Guanacos. After I arrived in Fiambalá, an attendant at a gas station accidentally filled the tank of my rented Toyota Corolla with diesel fuel. When the mistake came to light a few blocks down the road, I returned the car to the gas station. A Good Samaritan customer at the gas station helped me get my luggage (loaded with valuable cameras and other gear) to a $20 hotel down the street (which was actually fairly nice). I was concerned about what would happen if the car couldn’t be fixed and driven back to Buenos Aires. The next morning, a mechanic drained the tank through a hose attached under the back seat. To my great relief, the car ran well after the tank was filled with gas. After an amazing road trip, it was wonderful to make it back to Buenos Aires and then back home the next day (just in time for a family gathering for Thanksgiving).

Daytime Flight over the Amazon. I visited Brazil and Argentina in late May and early June of 2025. Photos and videos from the trip are presented in this video. Months of planning appeared to be in jeopardy when the flight from Miami to São Paulo was delayed until the following morning. In order to salvage the itinerary, we paid an extra $1,680 to get on a connecting flight that arrived at Foz do Iguaçu after midnight, but the delay turned out to be a blessing in disguise. Most flights to South America are at night. It was exciting to fly over the Amazon during the day and see the vast stretches of rainforest appearing in the above photos (click here to see a larger version).

Iguazu Falls. I visited Iguazu Falls on May 25 (Brazil side) and May 26 (Argentina side). The above photo shows the Garganta del Diablo (Devil’s Throat) from the Brazil side. This video shows footage of the falls from both countries and Coatis (or Ringtails) that serve as a cleanup crew on a shuttle train on the Argentina side. Each time the train stops, the Coatis come on board and scurry around under passengers’ feet looking for bits and pieces of food. They get off when the train is about to depart the station.

Bird photography. During the last week of May, I did some bird watching at Iguazu Falls and at parks in Campinas and Jundiaí. During the first week of June, Demis Bucci led me on a bird watching trip that included two nights at Ninho da Cambacica in Ubatuba (in the lowlands), two nights at Sítio Cotinga in São Luis do Paraitinga (more than 5000 feet above sea level), and various locations near and between those lodges. I used a Nikon Z6ii camera with a 400 mm f/4.5 lens. The above photo of a Long-trained Nightjar was taken with an ISO of 3200 and an exposure time of 1/50 of a second. The 224 species in the list below were seen or heard during the trip. Photos may be viewed by clicking on the highlighted species (and in this video). Near both lodges, I used a weather-proof audio recording system that is based on the Sony PCM-D100 and designed to operate for multiple days. Having previously used lead batteries as an external power source, I reconfigured with 28 AA batteries in order to reduce the weight of my luggage. This audio recording was obtained in the forest at Sítio Continga. Demis is an extraordinary guide in terms of his knowledge of the birds and ability to find them. Both lodges have excellent facilities, good food, and friendly hosts. View of the feeders at Ninho da Cambacica. View over the surrounding landscape from the lodge at Sítio Cotinga. The single-unit lodge at Sítio Cotinga sits alone, above and away from the other facilities. While using my laptop late one night, I noticed a moving shadow in the corner of my eye. Since it was dark outside, this meant there was an animal inside! It turned out to be a house cat that must have entered hours earlier, when the door was left open to let in some cool air.

Magnificent Frigatebird,

Anhinga,

Neotropic Cormorant,

Buff-necked Ibis,

Black-crowned Night-Heron,

Rufescent Tiger-Heron,

Snowy Egret,

Great Egret,

Cattle Egret,

Cocoi Heron,

Muscovy Duck,

Brazilian Teal,

Black Vulture,

Turkey Vulture,

King Vulture,

Snail Kite,

Short-tailed Hawk,

White-tailed Hawk,

Roadside Hawk,

Savanna Hawk,

Laughing Falcon,

Crested Caracara,

Yellow-headed Caracara,

Limpkin,

Red-legged Seriema,

Wattled Jacana,

Blackish Rail (heard),

Slaty-breasted Wood-Rail,

Common Moorhen,

Purple Gallinule,

Southern Lapwing,

Ruddy Ground-Dove,

Ruddy Quail-Dove,

Eared Dove,

White-tipped Dove,

Gray-fronted Dove,

Rock Dove,

Plumbeous Pigeon,

Picazuro Pigeon,

White-eyed Parakeet,

Maroon-bellied Parakeet,

Cobalt-rumped Parrotlet,

Plain Parakeet,

Yellow-chevroned Parakeet,

Turquoise-fronted Amazon,

Scaly-headed Parrot,

Smooth-billed Ani,

Squirrel Cuckoo,

Tawny-browed Owl,

Burrowing Owl,

Long-trained Nightjar,

Scale-throated Hermit,

Reddish Hermit,

Saw-billed Hermit,

Violet-capped Woodnymph,

White-chinned Sapphire,

Versicolored Emerald,

Purple-crowned Plovercrest,

Festive Coquette,

Glittering-throated Emerald,

Sapphire-spangled Emerald,

Sombre Hummingbird,

Brazilian Ruby,

Green-backed Trogon,

Surucua Trogon,

Amazon Kingfisher,

Green Kingfisher,

Rufous-tailed Jacamar,

White-eared Puffbird,

Chestnut-eared Aracari,

Channel-billed Toucan,

Red-breasted Toucan,

Toco Toucan,

White-barred Piculet,

White-browed Woodpecker,

White-spotted Woodpecker,

Green-barred Woodpecker,

Campo Flicker,

Blond-crested Woodpecker,

White Woodpecker,

Yellow-fronted Woodpecker,

Lineated Woodpecker,

Olivaceous Woodcreeper,

White-throated Woodcreeper,

Lesser Woodcreeper,

Narrow-billed Woodcreeper,

Scalloped Woodcreeper,

Araucaria Tit-Spinetail,

Wing-banded Hornero,

Rufous Hornero,

Rufous-capped Spinetail,

Pale-breasted Spinetail,

Spix’s Spinetail,

Yellow-chinned Spinetail,

Pallid Spinetail,

Rufous-fronted Thornbird,

Orange-eyed Thornbird,

Orange-breasted Thornbird,

Firewood-Gatherer,

Pale-browed Treehunter,

Buff-fronted Foliage-Gleaner,

Sharp-tailed Streamcreeper,

White-eyed Foliage-Gleaner,

Streaked Xenops,

Giant Antshrike,

Tufted Antshrike,

Large-tailed Antshrike,

Chestnut-backed Antshrike,

Variable Antshrike,

Plain Antvireo,

Unicolored Antwren,

Streak-capped Antwren,

Ferruginous Antbird,

Bertoni’s Antbird,

Rufous-tailed Antbird,

Ochre-rumped Antbird,

Scaled Antbird,

White-shouldered Fire-Eye,

Dusky-tailed Antbird,

Rufous-capped Antthrush,

Rufous-tailed Antthrush,

Rufous Gnateater,

Black-cheeked Gnateater,

Pin-tailed Manakin,

White-bearded Manakin,

Swallow-tailed Manakin,

Serra do Mar Tyrant-Manakin,

Buff-throated Purpletuft,

Chestnut-crowned Becard,

Planalto Tyrannulet,

Gray-headed Elaenia,

Small-billed Elaenia,

Yellow Tyrannulet,

Gray-backed Tachuri,

Southern Beardless Tyranulet,

Serra do Mar Bristle-Tyrant,

Gray-hooded Flycatcher,

Sepia-capped Flycatcher,

Bran-colored Flycatcher,

Fork-tailed Pygmy-Tyrant,

Ochre-faced Tody-Flycatcher,

Gray-headed Tody-Flycatcher,

Black-tailed Flycatcher,

Cliff Flycatcher,

Vermilion Flycatcher,

Blue-billed Black-Tyrant,

Crested Black-Tyrant,

Yellow-browed Tyrant,

Gray Monjita,

White-rumped Monjita,

Streamer-tailed Tyrant,

Shear-tailed Gray Tyrant,

Masked Water-Tyrant,

Long-tailed Tyrant,

Cattle Tyrant,

Social Flycatcher,

Great Kiskadee,

Boat-billed Flycatcher,

Tropical Parula,

Golden-crowned Warbler,

White-browed Warbler,

Riverbank Warbler,

Chivi Vireo,

Southern Yellowthroat,

Rufous-browed Peppershrike,

Rufous-crowned Greenlet,

Lemon-chested Greenlet,

Blue-and-white Swallow,

Brown-chested Martin,

Southern Rough-winged Swallow,

Long-billed Wren,

House Wren,

Long-billed Gnatwren,

Rufous-bellied Thrush,

Pale-breasted Thrush,

Creamy-bellied Thrush,

White-necked Thrush (heard),

Chalk-browed Mockingbird,

Crested Oropendola,

Golden-winged Cacique,

Red-rumped Cacique,

Chopi Blackbird,

Shiny Cowbird,

Giant Cowbird,

Variable Oriole,

Yellow-rumped Marshbird,

Cinnamon Tanager,

Black-goggled Tanager (female),

Orange-headed Tanager,

Hooded Tanager,

Olive-green Tanager,

Brazilian Tanager,

Sayaca Tanager,

Azure-shouldered Tanager,

Golden-chevroned Tanager,

Palm Tanager,

Flame-crested Tanager,

Ruby-crowned Tanager,

Burnished-buff Tanager,

Brassy-breasted Tanager,

Green-headed Tanager,

Red-necked Tanager,

Diademed Tanager,

Fawn-breasted Tanager,

Bananaquit,

Red-crowned Ant-Tanager,

Green-winged Saltator,

House Sparrow,

Blue Dacnis,

Green Honeycreeper,

Violaceous Euphonia,

Chestnut-bellied Euphonia,

Chestnut-vented Conebill,

Grassland Yellow-Finch,

Saffron Finch,

Curl-crested Jay,

Plush-crested Jay,

Double-collared Seedeater,

White-bellied Seedeater,

Rufous-collared Sparrow,

Buff-throated Warbling Finch,

Grassland Sparrow,

Hooded Siskin,

Half-collared Sparrow

As with all other living things, humans have traits that were molded by natural selection. In the struggle to survive, early humans needed robust senses and other physical traits in order to find food and avoid predators. After the advent of civilization, many of the factors that shaped us into what we are ceased to exist. Without those factors to keep the gene pool strong, certain traits (such as vision, hearing, strength, balance, and stamina) would be expected to degrade. As discussed here, this gradual loss of genetic information could have a profound effect on our species in the long run. This topic may be thought of in terms of a mathematical model in which the populations and traits of species are governed by a system of equations. A few simple examples are illustrated in the figures above. On the left is a solution of Volterra’s prey-predator equations in which there are periodic variations in the populations of the prey (solid curve) and the predator (dashed curve). The predator benefits from an increase in the population of the prey, but with a slight delay. After the population of the prey is reduced by predation, the population of the predator declines, and the cycle repeats. On the right is a slightly more complicated model in which the quality of the habitat degrades with time, making it harder for the prey to hide from the predator. In this case, the degraded habitat causes a decline in both populations. Although it would be difficult to explicitly formulate a model that accounts for a complex ecosystem that includes humans, mathematical modeling concepts can be useful for gaining insights into such an ecosystem. In natural selection, the traits of a species arise in response to factors related to interactions with other species and the environment. Such factors can be represented by forcing terms in a mathematical model. Although the dawn of civilization didn’t mark the end of all natural selection in humans, it was inevitable that certain survival-related traits would be gradually dulled or lost after the forces that molded them ceased to exist.

After seeing spectacular auroras during sea trips to the Arctic in 2014 and 2016, I wanted to go back and get some photos. I obtained these photos during subsequent trips to the Arctic. On land, it’s possible to get nice photos of auroras by taking long exposures with a camera mounted on a tripod. I wanted to find an approach that would work on a moving ship. The DJI Osmo+, which appears on the right in this photo, seemed to be a possible solution. While testing this hand-held device by moving my arm to simulate motion on a ship, I was encouraged to see that the gimbal appeared to keep the camera aimed in the same direction. The camera on the Osmo+ isn’t very good, but it does allow long exposures. I decided to try it during a sea trip to the north of Alaska in the fall of 2017. After the promising tests before the trip, I was surprised to see star tracks in the photos. During a trip to Harstad (in the ‘aurora belt’ in northern Norway) in the fall of 2022, I tried the Osmo+ on land and once again obtained photos with star tracks. During a trip to Harstad in the fall of 2023, I finally obtained some nice photos with a Nikon Z6ii camera and a NIKKOR 20 mm f/1.8 lens. I returned to Harstad for a sea trip in the fall of 2024. The Kp index was very high on some nights, and the auroras were the most colorful I have ever seen (as in the photo above). I tried using the Nikon mounted on a tripod on the deck of the ship and got some nice photos despite the motion. After returning from that trip, I obtained the DJI RS 4, which appears to the left of the Osmo+ in this photo. The RS 4 works on the same principle as the OSMO+ but is vastly superior to that device. The Osmo+ comes with a mediocre camera, which is the only option with that device. The RS 4 is a much more substantial device that can be used with a high-quality camera. During testing with the RS 4 and the Nikon (again moving my arm to simulate motion on a ship), I obtained long exposures of the night sky without star tracks, which suggests that this setup will make it possible to obtain nice aurora photos on a moving ship. Although the performance of the Osmo+ was disappointing for photographing auroras, this device is great for getting stable videos, such as this footage that was obtained from a boat in the Pearl River swamp.

My interest in night-time photography started with auroras and then expanded into other subjects. Anyone with even a slight interest in night-time photography has taken photos of the Moon and Milky Way. I recently obtained a Vespera II smart telescope. I haven’t yet had an opportunity to use it under ideal conditions, but even with light pollution it produced nice photos of the Andromeda Galaxy, Whirlpool Galaxy, Hercules Cluster, Orion Nebula, Trifid Nebula, Eagle Nebula, Lagoon Nebula, and Omega Nebula. The inset photo above was over-exposed in order to show the part of the Moon that is illuminated by sunlight reflected from the Earth. It has a pale blue appearance, as would be expected since the Earth is a “pale blue dot,” as Carl Sagan described it. While the Moon orbits the Earth, an observer on the Earth sees the phases associated with the sunlit side of the Moon. There are also phases associated with the earthlit side of the Moon, but they’re not visible from the Earth. As shown in the illustration above, both types of phases would be visible to an observer in an orbit around the Moon. Such an observer would also see parts of the Moon that aren’t illuminated, which are never visible to an observer on the Earth. During a trip to the north of Alaska in 2016, I obtained this photo of a half Moon that appears just above the horizon with the terminator oriented nearly vertically (such a photo is possible only in the Arctic). I used indirect lighting to obtain a photo of a farm house with the Milky Way in the background. This photo of Christmas lights was taken with a long enough exposure to show the tracks of raindrops from the headlights of a car (there is a rainbow-like feature in the puddle to the left). A long exposure was used to obtain this photo of night-time traffic.

Excellent photo opportunities often arise around the times of sunrise and sunset. The above photos were obtained during a stunning sunset near the Badlands of South Dakota. The top photo is the view looking in the direction of the Sun. The bottom photo is the view looking in the direction opposite the Sun. I was initially puzzled after noticing the beams converging in the direction opposite the Sun, but this is how they should appear. Since the beams are nearly parallel while crossing the sky, they appear to converge to a vanishing point when viewed in either direction. Another counterintuitive phenomenon that occurs near sunset is illustrated in this diagram. Since the Sun and Moon have about the same apparent diameter, it’s natural to get the impression that they’re about the same distance from the Earth. If they were, the half Moon would appear more than half illuminated as indicated on the left in the diagram. The right side of the diagram indicates the correct geometry. By looking up at the half Moon and applying the logic in the diagram, the ancients could have concluded that the distance to the Sun is many times the distance to the Moon and that the Sun is many times larger than the Moon. In 2013, I filmed a ‘binary star’ sunrise during a partial eclipse. The Sun appeared as a crescent, with its corners appearing as two bright point sources below a thick deck of clouds on the horizon. One of my most memorable sunrises is this one during a transit of Venus on June 8, 2004. I observed this sunrise on the way out to sea from Ålesund, Norway. Among the most gorgeous sunsets I have seen are this one in Utah and this one in Pensacola (note the crescent Moon to the upper left). This photo was obtained near Flaming Gorge just before sunset. Even when the Sun barely gets above the horizon in the Arctic, it can put on colorful displays, such as during this sunset. I will never forget this sunset during my final visit to English Bayou in June 2013 to close out eight years of field work in the Pearl River swamp. This photo was obtained during a spectacular sunset in the Thousand Islands. This photo was obtained in Monument Valley just before sunset. In Virginia, I have photographed peaceful, turbulent, and fiery sunsets. Some of the best rainbows, such as this one, are visible just before sunset.

North of Norway (Fall 2024). During the fall of 2024, I participated in a sea trip that originated in Harstad, Norway, on September 27, passed near Svalbard (which appears in the above photo), turned west toward Greenland, went as far north as 78.5°, and ended back at the starting point on October 9. I obtained photos and videos with a Nikon Z6ii, lenses ranging from 20 to 400 mm, a DJI Phantom 4 Pro drone, and a Sony 4K video camera. Among the highlights of the trip were about seventy Ivory Gulls, nice views of the desolate coast of Svalbard, sea ice, and stunning auroras. Despite the motion of the ship, I obtained some fairly nice photos of the auroras by mounting the camera on a tripod on the deck. There were amazingly colorful auroras as we approached Norway from the northwest during the final leg of the trip. Photos and videos from the trip are presented in this video.

North of Alaska (Fall 2017). During the fall of 2017, I participated in a sea trip to the north of Alaska and obtained lots of

photos and video footage. The videos may also be accessed in

this playlist on YouTube. The trip began in Dutch Harbor on October 18 and ended in Seward on November 8. This map shows the trip back to the south.

I obtained photos of auroras from the ship with a DJI Osmo+, a camera with a gimbal that can be used for long exposures on a moving platform. Among the highlights of the trip were observing sea ice, the auroras, and the amazing flights of albatrosses, going through the Unimak Pass, and seeing for the first time the Alaska Peninsula, Kodiak Island, the Kenai Peninsula, Seward, Denali, and Anchorage.

This image of an apparent Ivory Gull is from the 11:44 mark in this video (the bird is flying from left to right near the top edge of the picture).

North of Alaska (Fall 2016). During the fall of 2016, I participated in a sea trip to the north of Alaska and obtained lots of

photos and video footage. The videos may also be accessed in this playlist on YouTube. As shown on this map, the trip began in Nome on October 15 and ended in Dutch Harbor on November 11. Most of the trip was above the Arctic Circle, and we got up to 75° N. Some of the highlights of the trip were a Gyrfalcon, an Ivory Gull (see the above photo), and twenty-one Ross’s Gulls that were in migratory flights to the west. Some of the video footage was obtained with a DJI Phantom 3 Pro drone, but it was usually too windy for it. Several months of acoustic data were obtained on hydrophones that were deployed during this trip. Some audio recordings from under the ice may be accessed through this article.

North of Norway (Winter 2014). During the winter of 2014, I participated in a sea trip off the coast of Norway and obtained lots of photos and video footage. The videos may also be accessed in this playlist on YouTube. As shown on this map, the trip began in Ålesund on February 18 and ended in Tromsø on March 9. Most of the trip was above the Arctic Circle, including several days above the northernmost tip of Norway up to nearly 72° N. Only a few people went ashore during a brief stop at Honningsvåg, but it was interesting to see that town from the ship. The video footage was obtained using bino-cam, which consists of a video camera mounted on binoculars. The binoculars provide a better image than the viewfinder and make it easier to get the camera on a bird. I saw a gull that seemed different from all of the common species that were seen regularly during the trip and suspected it was an Ivory Gull while watching it through the binoculars. It was exciting to see flocks of alcids with stunning Arctic scenery in the background. I never got tired of watching fulmars in flight. The northern lights were indescribably amazing on some nights, with some of the glowing green arcs passing directly above and extending from one horizon to the other.

During the last week of May 2014, I obtained lots of photos and video footage during a sea cruise from Seattle to Alaska with Holland America. The videos may also be accessed in this playlist on YouTube. I saw lots of seabirds during the transit from Seattle to Juneau, including several Black-footed Albatrosses, lots of Leach’s Storm Petrels, a few Fork-tailed Storm Petrels, several unidentified Shearwaters (some with white underwings and some with dark underwings), and many alcids. I saw lots of whales and other sea mammals at various points during the trip. My favorite part of the trip was going up Mt. Roberts in Juneau and seeing Rock Ptarmigans. I was expecting the ptarmigans to be in breeding plumage and was initially taken aback by the stunning white plumage. I heard one of them calling and the video shows the field marks well enough for positive identification. I was amazed by the flight and rapid bursts of wingbeats of that species. It was difficult to track a pair through the viewfinder of the video camera as they passed in front of patches of snow during a meandering flight. There was an amusing photo-bombing by a Bald Eagle during the filming of a singing Fox Sparrow. I was blown away by the beauty of Glacier Bay. It was the first time I was able to really study the Arctic Tern. I was amused to see a Black-legged Kittiwake resting on a small iceberg.

Wakefield Park in northern Virginia had lots of good habitat for migrating Connecticut and Mourning Warblers in the late 1990s. During that period, I searched that park for those species each morning during migration. I saw each of them ten times in 1998. I saw both species on the same day a few times. I saw three Connecticut Warblers one morning in 1999. A Mourning Warbler set up an out-of-range territory there in 2004. I searched for those elusive birds by relentlessly covering as much area as possible each day. Several years later, I used the same strategy to search for Ivory-billed Woodpeckers. In 1997, I visited southeastern Manitoba to observe Connecticut and Mourning Warblers on their breeding grounds. As June approached every subsequent year, I longed to return to the boreal forests of that region. I finally made it back up there in 2023. On a 4,000 mile road trip, I drove up the northwestern coast of the lower peninsula of Michigan, over the Mackinac Bridge, to the north of Lake Superior, and across Ontario through Thunder Bay and Kenora. I found dozens of Mourning Warblers but only one Connecticut Warbler, which was singing deep in a spruce bog to the west of Kenora. I initially decided not to venture out into the bog to see that bird. I was anticipating easier opportunities further to the west in Manitoba, but it turned out that an area where these birds nested in 1997 had been logged. Running short on time, I decided to backtrack to the site near Kenora, where the Connecticut Warbler was still singing! Having suffered a broken arm during a fall in 2007, I cautiously made my way out over the unstable ground in the bog. I obtained more than ten minutes of video with a handheld 4K camera. It was hard to hold the camera steady while standing on unstable ground and with the lens on full zoom, but DaVinci Resolve did a nice job of removing the effects of camera motion. I also got some footage of a Spruce Grouse. Over and over, I aimed the video camera in the direction of a singing Mourning Warbler that seemed to be invisible. This photo gives an indication of how well these birds can blend into the vegetation. The camera picked up that bird, but my eyes missed it.

During the summer of 2024, I took a 17,964 mile road trip across North America. Photos, videos, and audio recordings from the trip are presented here. The purposes of the trip were to look for Connecticut Warblers and other birds and enjoy the scenery. Birds are most active and easiest to find in June, but higher elevations at some of the parks are closed until later in the summer. So it made sense to do the trip in two phases. I began the first phase, which appears (minus side trips to Glacier and Crater Lake National Parks and other sites) in the above map (click here for a larger version), in Alexandria, Virginia, on May 29. After stopping to visit relatives in Pennsylvania, I drove north to Kenora, Ontario, and then west to Riding Mountain National Park and Duck Mountain Provincial Park in Manitoba. After going south to see relatives in Montana, I drove back north to Prince Albert National Park in Saskatchewan and then west to Jasper and Banff National Parks in Alberta and British Columbia. I made a stop near the northern tip of Idaho to deploy a game camera that transmits photos by cell and has a solar panel. I then drove back into Montana to Glacier National Park. After a brief stop to reposition the game camera, I headed west to Seattle, Olympia, Portland, Crater Lake National Park in Oregon, Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park in northern California, and Tallimook in Oregon. During the trip back to the east, I visited Powder Mountain and Great Salt Lake in Utah, Dinosaur National Monument in Utah and Colorado, and Ft. Riley in Kansas. The trip odometer read 11,452 miles when I arrived back in Alexandria just after midnight on July 2. During the second phase of the trip in August, I visited Yellowstone National Park, returned to Idaho to upgrade the game camera setup, visited areas in Glacier National Park that were closed in June, and revisited Dinosaur National Monument. I drove 6,512 miles during the second phase for a total of 17,964 miles. During a 12,500 mile road trip in 1997, I didn’t own any cameras. For this trip, I had a Nikon Z6ii, 400 and 560 mm lenses, a 24 to 200 mm zoom lens, a DJI Phantom 4 Pro drone, a Sony PCM-D100 audio recorder, and a Sony 4K video camera.

In the spring of 1997, I did a 12,500 mile (the distance between the North Pole and the South Pole) birding watching trip around the U.S. and partially into Canada. Click here for a larger version of the above map (which excludes side trips to Yellowstone National Park and other sites). This report contains a day-by-day account of the locations that were visited and the birds that were seen. These reports contain accounts of some of my other bird watching trips. I started in Virginia on May 3 and headed south to Florida; then west through Louisiana, Texas, and Arizona; north through New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana; back to the east through North Dakota, Manitoba, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan; and finally back to Virginia on June 13. I did the trip in my 1979 Ford Fairmont two years after rebuilding its engine. By sleeping in the car, I saved money and woke up most days near prime areas for birds. The trip cost about $800 in gas and less than $500 for food, day-use fees, and other expenses. Two of the highlights of the trip were my first visit to southeastern Arizona and seeing a Connecticut Warbler singing in its breeding territory. On a typical day, I looked for birds from before sunrise until after sunset, drove several hundred miles between sites at night, slept for a few hours curled up on the front seat, and repeated this the next day. I lived off cereal with water, juice, granola bars, raisins, junk food, and adrenaline. I had a great time while seeing 383 species of birds and lots of gorgeous places.

I went to Norway in October 2023 to see auroras. I obtained photos using a Nikon Z6ii camera with a NIKKOR 20 mm f/1.8 lens. I obtained video footage of gorgeous scenery using a DJI Phantom 4 Pro drone. Bad weather was predicted for all five nights of the visit, but I saw some nice auroras over Greenland during the flight across the Atlantic. I was elated to see clear skies as the flight came in for a landing at Harstad, which is located in the aurora zone and has excellent accomodations. The above photo was obtained that night. A high-resolution version may be viewed here. Many aurora photos and drone scenery of the Lofoten Islands and other nearby areas appear in this movie. Drone footage of Harstad appears in this movie.

I watched the eclipse of April 8, 2024, just to the east of Ash Flat, Arkansas. I obtained photos using a Nikon Z6ii with a NIKKOR 400 mm f/4.5 lens with a 1.4X extender to 560 mm. I used exposure bracketing to capture different parts of the corona. The above photos were obtained using an ISO of 400, an aperture of f/11, and exposure times of 1/250, 1/125, 1/60, 1/30, 1/15, 1/8, 1/4, 1/2 and 1 second. Prominences are visible in this photo, which was obtained with an exposure time of 1/250 second. The prominence near the bottom in that photo was easily visible to the naked eye during the eclipse. Details of the corona further from the Sun are visible in this photo, which was obtained with an exposure time of 1/2 second. I used a DJI Phantom 4 Pro drone to obtain video footage of the distant sky in the direction of the approaching shadow. In the first part of the video, totality is far off, and the distant sky appears dark. Later on, the ground near the drone gets darker, and the distant sky gets brighter as totality comes to an end far in the distance. The shadow moves several times faster than a jet liner, but its trailing edge can be seen approaching in the video.

I watched the eclipse of August 21, 2017, near the Boysen Reservoir just to the north of Riverton, Wyoming. My primary objective was to film the approaching shadow with a drone, but I brought along a Sony HDR-HC5 video camera. Since totality would last for only a few minutes, I decided on a plan that would allow me to start the drone and video camera and then focus on enjoying the spectacle. Ten minutes before the start of totality, I launched the drone and left it hovering at an altitude of 120 meters. Immediately after the start of totality, I aimed the video camera at the Sun and left it recording from a tripod. It’s easy to see the motion of the shadow by scrolling back and forth through the drone footage, which may also be viewed at normal speed. The other video shows features of the corona that appear in high-quality images. During the partial phases of the eclipse, there were obvious drops in temperature and light, as illustrated in these photos.

In June 2019, I visited Manú National Park in Peru and obtained lots of photos, video footage, and audio recordings. I stayed at Cock-of-the-Rock Lodge on Manú Road in the cloud forest and Amazonia Lodge near Rio Madre de Dios in the lowland forest. I used a DJI Phantom 4 Pro drone to obtain video footage and images of the forest habitats and a Sony PCM-D100 to obtain audio recordings.

In July 2003, I visited the Peruvian Amazon and Machu Picchu. I entered Manú National Park with a small tour group and visited Huarcapay, many areas on Manú Road, Amazonia Lodge, the river below Atalaya, and Pantiacolla Lodge. Despite having problems with my camera, I managed to get some fairly good photos such as the one above of a Golden-headed Quetzal.

In April 2000, I made my first trip to South America. After attending a conference in Trujillo, Peru, I rented a car and drove over the Andes and into the jungle. One of the highlights of the trip was getting my first view of the Amazon River (the Rio Marañon branch) as shown in the above photo. I had an unnerving encounter with natives in the jungle, but it was an amazing experience to get my first taste of the Amazon and see stunning birds such as the Paradise Tanager. This report contains an account of the trip and the birds that were seen.

In July 2002, I obtained some photos at Iguazu Falls, which are the largest in the world by flow rate. They are located in the border region between Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay. The falls and surrounding tropical forest are one of the most beautiful places in the world. Watching the water thunder over the falls in the Garganta del Diablo (Devil’s Throat) is a stunning sight. This report contains an account of the trip and the birds that were seen.

For many wave propagation problems in geophysics and planetary physics, it is necessary to take into account the fact that the medium varies in the horizontal directions. In the ocean acoustics example on the above left, the bathymetry varies in the horizontal direction. In the seismology example on the lower left, the topography and thicknesses of layers of different types of rock vary in the horizontal direction. In the Jovian acoustics example on the right, the zonal winds vary with latitude. Such problems cannot be solved with analytical methods (separation of variables), and they are often too large to be solved directly with numerical methods. When the horizontal variations in the medium are sufficiently gradual, accurate solutions may often be obtained efficiently by applying a parabolic wave equation, which accounts for energy that propagates in the outward horizontal direction (energy that is backscattered toward the source is neglected). This approach and some of its applications are described in Parabolic Wave Equations with Applications. Much of the fruition of this work is discussed in this article.

Power rankings can be computed by assuming that each team has a power P and that the expected point differential in a game is the difference between the powers of the teams plus a home field advantage (HFA) factor. In this model, there is an equation for every game played during the season (272 games in 2024). The unknowns in these equations are HFA and the powers of the 32 teams. Although these equations don’t have an exact solution, the method of least squares can be used to obtain an approximate solution. This approach has been used to compute the power rankings for each season since 1945.

I didn’t have much interest in Rubik’s Cube when it first came out, but then it occurred to me that it’s a fascinating application of group theory. It was 1982, and I had recently been introduced to that topic in an algebra class at MIT. It didn’t take long to figure out how to solve it using commutators, conjugates, and the cycle notation. I was hoping that someone would generalize it to the dodecahedron. Such a puzzle, which is known as the Megaminx (shown above), was already available at the time, but I didn’t find out about it until decades later. I have posted a lecture on solving puzzles using group theory. FORTRAN codes for solving these puzzles on the screen are available for download.

My grandmother got me interested in coin collecting in the early 1960s. My favorite coin was the Buffalo Nickel (1913–1938), which was rapidly disappearing from circulation by the mid 1960s. In order to gain insights into the variation over time of the population of Buffalo Nickels in circulation (relative to the total number of nickels of all designs in circulation), I used a simple model in which 4% of all nickels disappear from circulation each year. I used the number of nickels produced each year since 1866 as inputs to the model. There is uncertainty in the attrition rate, which would be expected to vary with time (e.g., attrition increases as a design becomes rare and gets pulled from circulation at a higher rate). I decided to terminate the above graph at 1964, when the interest in coin collecting increased with the introduction of the Kennedy Half Dollar and the end of 90% silver coins. The prediction of a rapid decrease in Buffalo Nickels during the early 1960s is consistent with my experiences as a collector during that period. I also applied the model to all four nickel designs (Shield, Liberty Head, Buffalo, and Jefferson) and the Indian Head Penny (1859–1909), which I never found in circulation.

I have always been fascinated by mechanical objects, such as the internal combustion engine. At the age of twelve, I took apart and reassembled a lawn mower engine. Several years later, I developed an interest in Volkswagen engines, such as the one appearing in the above photo from 1979, which powered a 1966 Beetle that I used to drive back and forth between Florida and Massachusetts while attending MIT. After learning about Fourier series, I came up with an idea for a new type of internal combustion engine. In the Fourier engine, each combustion chamber is open to multiple pistons that operate at different rates. Different choices for the displacements and phases of the cylinders correspond to different volume curves (as in a Fourier series). It might be possible to increase power by designing an engine with a volume curve for which the duration of the intake and ignition strokes (which become less efficient as duration decreases) exceeds the duration of the compression and exhaust strokes. I modified the 1300 cc engine in the photo by installing an external oil filter, which is mounted on the fan housing. Oil filter kits for this type of air-cooled engine come with an oil cooler that is mounted over the air intake opening on the backside of the fan housing (one of the hoses attached to the oil filter goes to the cooler). In a stock Beetle engine, there is no oil filter, and the oil cooler is located inside the fan housing, where air that cools the cylinders on the left side of the engine passes through the oil cooler (and get warmed up slightly) before reaching the cylinders. The left side of a stock engine therefore runs hotter, and problems with valves are more common on that side. Installing an oil filter kit helps to extend the life of this type of engine. I drove this car hard on many long road trips without any problems.

Starting at the age of 15 in 1973, I spent several years doing construction work, including building fences (such as this one at my mother’s house in Tampa as shown after a rare snowstorm in 1977) and swimming pools (such as this one, where I’m dumping a wheelbarrow in 1977). At the age of 62, I helped out in a type of construction work in which I had no previous experience — installing a metal roof. As discussed here, it was interesting to see some of the problems that can arise in roofing and how to deal with them.

Many of my visits to Louisiana have coincided with Mardi Gras, which occurs during the most favorable months for searching for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. I obtained video footage of the Zulu (2013), Endymion (2013), and Endymion (2025) parades in New Orleans. I used a drone to obtain video footage of the Selene (2019) and Slidellians (2019) parades in Slidell. I also obtained video footage of some ingenious Louisiana Pelican Art in Slidell.

In August 2019, I obtained lots of photos during a 5000 mile road trip to Montana that included visits to the Badlands, Black Hills, Yellowstone National Park, Grand Teton National Park, Wind River Canyon, North Platte River, and Iowa State Fair.

During a visit to Arizona, I spent a day each in the Chiricahua and Huachuca Mountains in the southeastern corner of the state and also visited Monument Valley and Petrified Forest National Park. Some photos of the gorgeous scenery are posted here. I had a bit of an adventure during a hike around Carr Peak. On the way up a steep trail to Bear Saddle, I got severe cramps in my thighs and had to use up most of my fluids in order to stop them. I was beyond the half-way point of the hike and decided to keep going. When the trail got steeper and the cramps returned, I decided to turn back. The trail ahead was uncertain, and I knew there was a stream with water on the way back. I wouldn’t have made it out of there if not for that stream.

I spent several days in Colorado at the end of June 2014. I obtained photos and video footage of flowers and the glass artwork of Dale Chihuly at the Denver Botanical Gardens and of wildflowers, wildlife, and scenery in the mountains in Golden Gate Canyon State Park and Rocky Mountain National Park.

In August 2015, I took a cruise out of Kingston, Ontario, that sailed through the 1000 Islands and made stops at Upper Canada Village, the observation tower near the international bridge, and other locations. Some photos are posted here.

In October 2020, I used a drone to obtain images of the autumn foliage in the Appalachians of Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee. The images may be viewed in high resolution here and in a slideshow here. This project nearly came to an end when I crashed the drone into a tree. As can be seen in this image, however, I was very fortunate that small branches gently caught the drone with no damage other than a broken prop.

Radford High School Basketball

Photos from the Four Corners area

Photos from Big Bend National Park

Photos from Yellowstone National Park

Wakefield Park: A Hotspot for Mourning and Connecticut Warblers